James Grose slides into a chair and cruises readily through a series of questions you know he’s answered many times before. He has an affability and boyish energy which, despite his late-forty-something years, he wears with ease. He’s also a natural talker. It has been said, he quips, that he talks too much. But he speaks well and his enthusiasm is engaging. At the same time, he is unassuming and explains his work with the sweeping strokes of thorough consideration.

March 10th, 2014

“If there wasn’t clarity in my working life, I would think I had failed. There’s a lineage to your work,” he says, “starting off even when you’re a child, right through to the way that you finish your last project.” It’s through this continuity, he suggests, that integrity, reality and substance emerge.

In one sense, Grose’s career as an architect has been marked by twists and turns. He began studying architecture straight out of school, but completed a course in industrial design. He furthered his industrial design studies in Sweden, but never practised. Instead, he worked for some years as a graphic designer before his interest in architecture was re-ignited. Returning to university, he qualified as an architect – 13 years after setting out.

Initially, he made his name designing houses in partnership with his wife, Nicola Bradley. Ten years later, as an acclaimed small practitioner, he leapt into the big end of the profession.

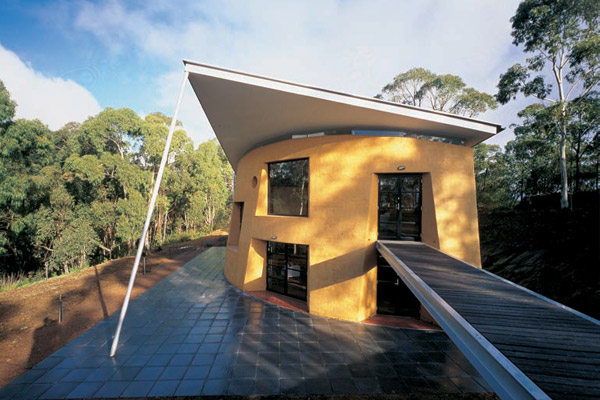

Newman House, Wollongong. Grose Bradley, 1992. Photo: John Gollings

Growing up in the Queensland coastal town of Bundaberg, his memories are of the simplicity of small town life, the steaming heat, the landscape and the bush, making billy-carts and canoes, surfing and drawing. His father is a painter and, for Grose, architecture seemed the logical course. “God, what can he do? Can’t be a scientist. Can’t be a lawyer. He draws!” “[Some] people tend to have a natural inclination toward making things,” he says, “so you end up in that bin of people.”

At the Queensland Institute of Technology, he embraced the ideas of architect and academic, Eddie Codd, who ran the architecture school. “He pushed a line against the idea of architecture being elitist, that it’s more about making things, a production mode.” Grose developed a fascination with mass production, technology and fabrication (“how things screw together”), which led him into the industrial design stream that was included as part of the course. He remembers “Edward de Bono’s first book, The Art of Lateral Thinking, was our sort of Bible.”

At the University of Gothenberg he experienced the Swedish design environment. “Not design with a capital D that you find in magazines: You want style? Get Design! [In Sweden] design is absolutely fundamental to everything, implicit to existence. People weren’t talking about the way things looked; they were talking about the way things worked. So, coming back to making architecture after industrial design, sure, you become involved in the way a thing looks, but your primary investigation is how it works.”

Levings House, Carey Gully, South Australia. 1997. Grose Bradley

Grose also had an interest in graphic design and it was through this graphic work – designing Architecture Australia magazine for some years and meeting a lot of architects – that he returned to architecture. At Sydney University he was impressed by the divergent views of Col Madigan and Harry Seidler. “Just after that I met Glenn [Murcutt]. These three people very much affected the way I thought about architecture. It was a fantastic experience to have that contact.”

After graduating with Honours in 1984, he worked with Noel Robinson, then Bligh Robinson, in Sydney, and in 1988 formed a partnership with his interior designer and subsequently architect wife, Nicola Bradley.

In fact, Grose Bradley’s first clients, the Newmans, came referred by Murcutt, whose assistance and influence Grose acknowledges as fundamental to his career. “I owe an enormous debt to him.” The highly distinctive and award-winning Newman House, Wollongong, set the tone for things to come and very quickly Grose had an architectural reputation and a blossoming career. A progression of noted houses followed along with a couple of re-cycled industrial buildings and the Architecture Studios at the University of Newcastle. In his introduction to Grose Bradley, The Poetics of Materiality, John Hockings writes of Grose’s developing architectural preoccupations with “the qualities of the Australian landscape, with light, and with industrialised structure, fabric and form.”

Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture, Canberra. Bligh Voller Nield, 2002

“To use good old 20th century manifesto jargon, the house is the program of architecture, because it’s where you deal with small groups of people, human scale, and the very act of domesticity,” says Grose. “Houses are about intimacy and warmth and safety, mental or intellectual and emotional security and placement in the world. When you design a house you design absolutely for a family and the dynamics within a family and the joy is in making a thing that is absolutely engaged with [them] – a house that fits them like a glove. So, although there are clear and obvious consistencies, like dealing with the manipulation of light and air and vistas and materiality, the way you assemble them is different for each solution.”

“A house is a fantastic thing to design because it teaches you about life [and it’s] incredibly complex because it’s one-on-one – you’re a psychologist in some ways – and you really work hard to find that glove, the perfect fit. Also, as architecture, it’s got to work at every level: for the kids, for the grown-ups, for twenty years, for corrosion, with the garden, with the street, with the environment. Sure, all those things occur in bigger buildings too, but because it’s [the family’s] money, it’s not a corporation’s money, it’s a very emotional thing.”

Many of the houses Grose has designed are in the country, where he’s been able to explore the relationship between building and the landscape. Underpinning his consciousness, like that of other architects from Queensland is a feeling for the landscape and for the Australian vernacular. Hockings writes that Grose absorbs the landscape “with a sculptor’s eye and a poet’s heart.” Grose sees the landscape in the broadest sense, meaning place, as an omnipresence that dominates our experience. “The relationship between nature, or the land, is endemic to all things in Australia,” he says. “We’re very much engaged in the landscape, even if it’s in a more abstract way in the city. The land is certainly what drives my core interest in making things.”

Newman House, Wollongong, Grose Bradley, 1992. Photo: John Golling

“Architecture is really about trying to understand place. But place is not just a physical thing. Place is nothing without people or culture.” Fundamentally, then, Grose’s architecture is designed to acknowledge and heighten the sense of place – the inherent natural experience of space, air, sun, light, temperature and views, along with the more abstract overlays of social, cultural and political meaning.

Hockings also speaks of Grose’s “poetic concern with the nature of material construction. Grose Bradley buildings are not simply about direct expression of material and structural frame. Rather they place the material quality of the architecture centre stage.” Self-evident is a term that recurs in Grose’s conversation. “Form should be self-evident and materials should be self-evident. It’s a bit like reading a human being. [They’re] either self-evident or they’re a pastiche, and you can tell. The analogy is that a building should be complete and whole, and honest, not only to itself but in its relationship with things around it.” And materials should be used to create “space which is fundamental rather than decorated.”

“Nicola Bradley has had a profound effect on the way that James Grose understands materials,” writes Hockings, introducing “him to the importance of material texture and the possibilities of more complex spatial organisations.”

While Bradley has since left the profession to pursue a career in librarianship, Grose credits her influence as “demonstrating to me the importance of thinking broadly; that quality lies in depth of thinking rather than gestural [solutions].”

By 1998, Grose was looking for bigger projects and new challenges and began discussing a merger with Bligh Voller Nield. At the same time, Rosemary Kirkby, who was managing the refurbishment of the MLC building in North Sydney, NSW, was on the lookout for a small practitioner with a residential sensibility, and a large firm with the capacity to deliver such a complex project. A ten minute meeting over a coffee proved to be yet another pivotal point for Grose, one which launched him, professionally, on a completely new scale. Grose ranks Kirkby as another major influence on his thinking. “Rarely do you find people who are as broad in their intellectual abilities as Rosemary,” he says.

Left: Newman House, Wollongong, Grose Bradley, 1992. Photo: John Golling

Right: Campus MLC. Bligh Voller Nield, 2002. Photo: Anthony Browell

With Kirkby as head of the team, and Grose as design director with Bligh Voller Nield, the project that became Campus MLC was significant. In giving physical form to MLC’s progressive, non-hierarchical corporate culture, the redesigned interior of the 1957 heritage-listed building was the culmination of a process of cultural change that Kirkby had been guiding for ten years. The kind of project that might otherwise have been considered a lowly office fit-out was transformed into a rich new arena of possibility. While principles of environmental psychology were being applied to workplace design in Northern Europe and Scandinavia, Campus MLC was the first of this kind in Australia.

Here, investigations into the psychological impact of the workplace on its users were designed to promote productivity, flexibility, egalitarianism, transparency and engagement. The brief called specifically for spaces that would “not conform to the norm.” Strategies to encourage interaction and relationships between users were central, as was an extensive consultative process. “We engaged the people who actually live here in all of these questions about design and that’s one of the reasons it feels so good. It’s about residential character. What we’ve really done is build big houses,” says Grose.

“It’s not what you’d call a high piece of design, but it’s not meant to be smarty-pants, look-at-me. It’s meant to be a serious place of habitation. On the other hand, it’s also fun.

So people don’t go in there and say what a fabulous design. They say it feels fabulous. And that’s a far better compliment. It’s a compliment to the team of people who put it together,” he adds, stressing the value of collaboration and the team structure. (He is critical of the notion of the architect as a guru in a beret dispensing creative genius.)

“Offices have been mechanically designed for so long, and now there’s a whole wave of interest in the workplace. The basic thesis is very simple. You take care of people’s needs – being a part of a community and being treated with dignity and respect – and they will make more money for you.” And the large corporations are getting it. The result, he says, has been “a complete sea-change in workplace design.”

Campus MLC has been acknowledged as the basis for the ‘future office’ in Australia and has spawned many spin-off projects in workplace design for Grose and Bligh Voller Nield. Refurbishment projects include Clemenger Advertising Agency, Deutschebank and the law firm, Baker McKenzie and Mallesons. Then came two new buildings, one for the ASB Bank in Auckland, designed with Jasmax Architects, and the other in Melbourne, the National at Docklands, with Rosemary Kirkby again leading the project. “They’re like dots that have been joined up along our journey here. But what started as an interiors project, turned into workplace design, then led to complete works of architecture – designed from the inside out – which are very rare.”

The $350 million National at Docklands project – 59,000 square metres in total – is due for completion in September 2004. “The National will be, not just the biggest [single] project of its type in the world worked on these sorts of principles, but it will be at the leading edge – one of the keystones of integrated workplace planning.”

As such, it presents a different model for making a city building. Creating community and building relationships remains pivotal. “The National is designed as a village, with a village square.” The approach allows leeway to explore his interest in sustainability and experience of place. The north-facing front of the building is designed as an eight-storey verandah to allow fresh air, sunlight and planting inside the building so people can re-engage with natural systems. The sheer scale of the project has also made much more research possible – internally with staff, nationally and internationally. “The [National] project is utterly unique, given the site, as well as the chemistry of the team – Rosemary’s team at the National and also our team, and the consultants.”

Rosemary Kirkby describes Grose as having a “willingness to listen and listen deeply” and tells how he moved effortlessly into MLC’s business and “learnt the language.”

“There’s a dignity about James. People trust him. They like to be around him. His capacity to be gracious under pressure is enormous. Everything is approached in a collaborative way. He’s a fantastic problem-solver. Nothing is too hard. And his ability to communicate is second to none,” she says. “Of all the teams in our organisation that have worked with him over the last five years, I think everybody would say that their lives have been richer as a result of knowing and working with James. I don’t think I’m saying that too strongly at all.”

The past five years working on these projects with Bligh Voller Nield have been “a fantastic experience” for Grose. “I have been able to understand more and more about making space, technically,” he says. He cites as examples two new buildings that are underway at the University of Newcastle. He is also enthusiastic about the Christian Centre in Canberra. “The little chapel, [which] is just stage one, is trying to suggest that implicit in spirituality is humility. It was very cheap, and it’s very raw and in-your-face,” he acknowledges. “It’s a challenging building.”

There are other projects too, but while he has continued to design houses under the Grose Bradley name since joining Bligh Voller Nield – all part of the agreement – the house beckons. “The more you understand about putting commercial or public buildings together you more you want to go back to the micro-problem, the house, and inject back into it the intellectual complexity that you develop from those other projects. I’m not sure that it’s going to happen, but that’s certainly the intent.”

Portrait by Anthony Browell.

James Grose was featured as a Luminary in issue #14 of Indesign, August 2003.

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

Within the intimate confines of compact living, where space is at a premium, efficiency is critical and dining out often trumps home cooking, Gaggenau’s 400 Series Culinary Drawer proves that limited space can, in fact, unlock unlimited culinary possibilities.

BLANCOCULINA-S II Sensor promotes water efficiency and reduces waste, representing a leap forward in faucet technology.

Elevate any space with statement lighting to illuminate and inspire.

In this candid interview, the culinary mastermind behind Singapore’s Nouri and Appetite talks about food as an act of human connection that transcends borders and accolades, the crucial role of technology in preserving its unifying power, and finding a kindred spirit in Gaggenau’s reverence for tradition and relentless pursuit of innovation.

With her recent registration, Tiana Furner is among the first cohort of Indigenous women registered as architects in Queensland and indeed Australia.

Construction is well underway at 3XN’s milestone project for the new Sydney Fish Market, designed with BVN and ASPECT Studios.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

Fluid and flowing, Cocoon is a school that, through its architectural form, enhances the day-to-day rituals of learning and elevates the experience for the very young.

The delectable bakehouse franchise has expanded its oeuvre with the addition and arrival of dual Sydney locations; here, we take a look at the flagship in Rosebery.