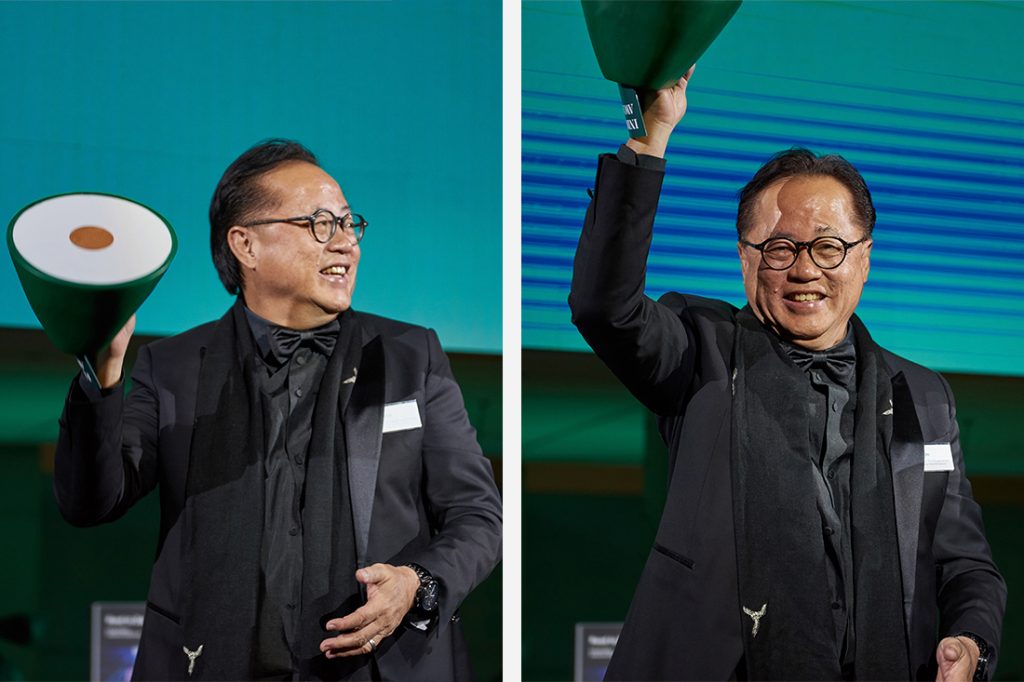

After winning the INDE.Awards Luminary People’s Choice trophy, Budiman Hendropurnomo of DCM Jakarta shared deep insight into practising in Indonesia during a special discussion at Saturday Indesign in Melbourne.

A united region is a strong region – this is a major theme underpinning the INDE.Awards program. And there is perhaps no better beacon for the value of shared understanding across the Indo-Pacific than someone who has spent their professional life straddling two of its countries.

Budiman Hendropurnomo accepting his award at the INDE.Awards 2019 Gala

Budiman Hendropurnomo is one of the most decorated and respected architects in Indonesia. He was born in Malang in East Java, and graduated from the University of Melbourne before joining Denton Corker Marshall (DCM) in Melbourne in 1981. He established DCM’s Indonesian office in Jakarta in 1983 (better known there as Duta Cermat Mandiri), and has since made this studio synonymous with large-scale projects that have helped shape the face of Indonesia – high-rise commercial towers, school complexes, shopping centres and seaside resorts.

Hendropurnomo travels to Melbourne regularly, and the Indesign Media team was delighted to have his presence in the southern city for the INDE.Awards Gala and Saturday Indesign in late June.

Narelle Yabuka with Budiman Hendropurnomo at the Brickworks showroom in Melbourne during Saturday Indesign

In a special discussion session at Saturday Indesign titled ‘The Long Game’, I had the honour of extending on our recent Cubes magazine profile on Hendropurnomo (‘The Long Game’ by Asih Jenie, Cubes issue 95) with a series of questions about aspects of practice in Indonesia, how this differs from the Melbourne experience, and the vast contextual changes that he has experienced throughout his career in Indonesia.

Here we present some key themes and excerpts from the conversation.

University of Multimedia Nusantara by DCM, Jakarta (2010–2013). Client: University of Multimedia Nusantara. Photography: DCM

The first Indonesian high-rise project that Hendropurnomo specified products for, circa 1983, revealed the constraints of the Indonesian construction market at the time beyond traditional modes of fabrication. “I remember, it was TOTO sanitary ware from Japan; they offered only two types of toilet in Indonesia. There was only one type of extruded non-slip ceramic in Indonesia, and that was it. Everything else came from overseas. The aluminium panels came from America, the glass came from Japan. It was quite amazing.”

He continued, “But right now, if I were building these towers, 95 per cent [of the materials and fittings] would be made in Indonesia… In 30 to 40 years, that’s how Indonesia has progressed.”

Kompas Multimedia Towers by DCM, Jakarta (2014–2018). Client: Kompas Gramedia. Photography: Tim Griffith

Yet, he noted, DCM’s research and development activities have remained in Australia. “A country like Indonesia cannot afford R&D. The R&D remains here [in Melbourne],” he revealed.

That said, there exists a wealth of knowledge within Indonesia that is regaining currency for a variety of reasons. Building and craft traditions in Indonesia have long been significant contributors to an expression of place, but also to a sensible mode of construction. “There’s growing concern now among younger architects that we should learn from our past – that the way we built in the past was sustainable,” said Hendropurnomo.

Maya Ubud Resort & Spa by DCM, Bali (1998–2001). Client: PT Hotel Pandan Arum. Photography: courtesy of DCM

“I mean, if you look at Maya Ubud, we did it almost 20 years ago and it’s very sustainable. At that time the currency suddenly went from $1 to 3,000 rupiah one week, to $1 to 15,000 rupiah the next week. Therefore, everything had to be local; there was no way that we could buy anything from overseas. So, the thatched roof was from a kilometre away. The stone cladding was from the river. The frame is bamboo, and it is naturally ventilated…

“If you look at traditional Balinese architecture, especially houses, that is how they were built. Now a lot of younger architects are looking at how we built in the past. You can design a modern form, but predominantly it should be ‘roof architecture’,” he said.

Maya Ubud Resort & Spa by DCM, Bali (1998–2001). Client: PT Hotel Pandan Arum. Photography: courtesy of DCM

Jakarta is at the forefront of the development of sustainable design regulation in Indonesia, suggested Hendropurnomo. For five years, between 2011 and 2015, he sat on an architectural advisory panel that reported to the governor of Jakarta on the suitability of large development proposals. “At that time we were also setting up the first [sustainability] regulations. It used to be, in the past, that everything was dictated by the private sector, by the developer… Before you didn’t have this body that scrutinised the building permits. Now it’s happening in the regions too. Slowly, Indonesia is developing toward more sustainable development.”

Maya Sanur Hotel Resort & Spa by DCM, Bali (2010–2014). Client: PT Hotel Pandan Arum. Photography: John Gollings

But developers are changing too. Southeast Asia is seeing a new cohort of clients as the second generation of family-run development companies gains influence. The members of the younger generation often study overseas, are well travelled and connected, and as a result, can have a significantly different perspective to their parents. I asked Hendropurnomo: Are they changing the playing field for architects in Indonesia?

Maya Sanur Hotel Resort & Spa by DCM, Bali (2010–2014). Client: PT Hotel Pandan Arum. Photography: John Gollings

“The change has been enormous,” said Hendropurnomo. “In the ’80s and ’90s you had first-generation developers. Their parents were poor as there was no money in the ’60s in Indonesia… Therefore, their mentality was that you build as cheaply and quickly as possible. But, their sons, daughters and grandkids have never been poor. They go out [of Indonesia] for university – they go to Berkeley and Harvard. When they come back, they become a better developer…

“So when we tell them, ‘Look, architecture should be sustainable now,’ …they understand that this is the new architecture. It uses less energy and you have a cooler environment – it’s good. So, right through Indonesia we are now getting a more sophisticated design, which is good for us as architects. If you can keep doing that, in the end we’ll get a better architecture, a better environment.”

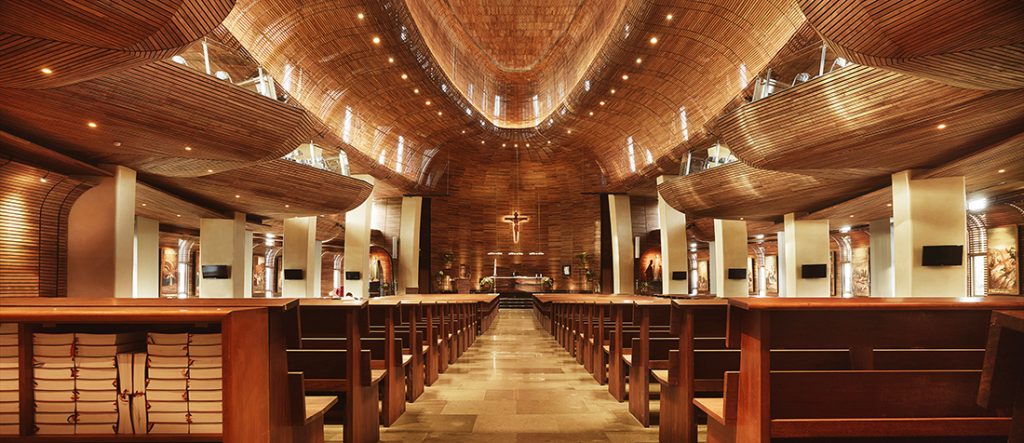

Gereja Stella Maris (Stella Maris Church), Renovation by DCM, North Jakarta (2011–2015). Client: Stella Maris Church. Photography: courtesy of DCM

Political and economic fluctuation and change make a particularly dramatic backdrop to practice in Indonesia, as epitomised by the currency shifts that precipitated the localised approach to materiality for the Maya Ubud project. Time can take on a life of its own as unexpected challenges arise. “Working in Indonesia can be like rowing through mud – you go two strokes forward and then one stroke backward. Sometimes it feels like one stroke backward all the time!” said Hendropurnomo, half in jest. “It seems to be easier here in Melbourne.”

Kempinski Nusa Dua by DCM, Bali (2003–2019). Client: Kempinski Hotels. Photography: courtesy of DCM

He elaborated, “Recently we completed the Kempinski Nusa Dua in Bali. It took 12 years to build this project, and within the 12 years things went up and down with the cycle of recessions.” But other factors were also at play. The Bali bombing occurred during the early stages of the project, resulting in unforeseeable complications with regard to site work – in particular the blasting of rock. “Our dynamite had to be kept by the police,” recalled Hendropurnomo, “locked up in the police station. The police had to bring it to site, then we could use it. It was a bad time, it was dangerous.”

UOB Plaza Office Tower by DCM, Jakarta (2002–2009). Client: PT Luminary Prima Group. Photography: DCM Jakarta

He reflected, “The bigger projects anywhere – in Melbourne or in Indonesia – are always prone to political changes. Had Jokowi lost this election, we would probably all drive taxis now because people would just stop investing. People wouldn’t believe in the economy anymore.”

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

With the exceptional 200 Series Fridge Freezer, Gaggenau once again transforms the simple, everyday act of food preservation into an extraordinary, creative and sensory experience, turning the kitchen space into an inspiring culinary atelier.

BLANCOCULINA-S II Sensor promotes water efficiency and reduces waste, representing a leap forward in faucet technology.

BLANCO launches their latest finish for a sleek kitchen feel.

Within the intimate confines of compact living, where space is at a premium, efficiency is critical and dining out often trumps home cooking, Gaggenau’s 400 Series Culinary Drawer proves that limited space can, in fact, unlock unlimited culinary possibilities.

In a climate of innovation, HDR’s architecture practice has forecasted six trajectories of change that will have a transformative impact over the coming year and redefine city-shaping for the foreseeable future.

In Australia alone, 6.4 per cent of all waste generated comes from furniture and furnishings. In this article, we review today’s most impactful Whole Of Lifecycle Furniture practices.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

Led by Hassell and The University of Melbourne’s Burnley Campus, the Melbourne Arts Precinct Plant Trials will evaluate over 1,000 plants under extreme conditions.

This interview with Koichi Takada, part of the SpeakingOut! series for the 2025 INDE.Awards, explores his organic design philosophy, architectural journey, and the inspiration behind Brisbane’s award-winning Upper House.